- Posted: July 18, 2016

- Filed Under: Environment

Movies have one job: to entertain us. Documentaries have a higher task: to entertain us and to be exact. Unfortunately, Stink! fails on the second count.

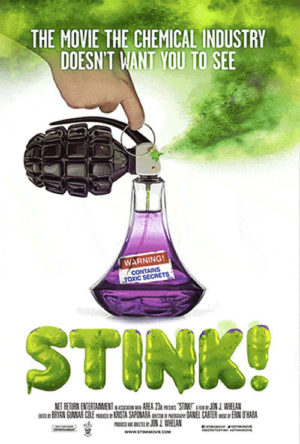

Stink! is about the quest of Big Apple-based Jon Whelan, a single father of two daughters who lost his wife to breast cancer, to figure out what chemicals are in household products and clothing. Often, one can simply look at the label and see, but as the film shows, it isn’t always so simple.

The documentary begins with Whelan attempting to figure out why his daughter’s new pajamas smell. He calls up the retailer, Justice, but isn’t able to get anywhere. (Did he really expect to find that answer with a random phone call to Justice? It’s like asking the cashier at Best Buy why the new iPhones only come it three colors.) Eventually, he sends the PJs off to a lab to get an analysis of what chemicals are present.

As the discussion unfolds, we learn several things. One is that while many chemicals must be on labels, “fragrance” can contain ingredients undisclosed on the label. In a short time, the film goes on to make the huge jump that chemicals are not properly safety tested, that we’re surrounded by chemicals that disrupt our bodies, and that chemicals may be behind the rise in rates of autism, obesity, cancer, and other maladies.

Well, that escalated quickly.

The film progresses into examining whether the government is too influenced by lobbyists to the chemical industry. In this formulaic big-bad-industry-plus-big-bad-lobbyists script, Stink! is hardly a pioneer, but Whelan does hound his targets, from a New Jersey Congressman to the head of a major chemical trade association. The film concludes with a call for transparency.

Analysis

Much of our problem with Stink! mirrors our issues with The Human Experiment: Alarmism masquerading as science. When dealing with chemicals, the dose makes the poison. Exposure to chemicals is inevitable in life, but what matters is how much. You can die from drinking too much water, after all, even though we need it to live. But it’s easy to lose rationality when presented with chemical names; for instance, people have signed a petition to ban the aforementioned dihydrogen monoxide.

Putting the film’s transparency argument aside for now, the notion that chemicals in household products are untested is simply not true. For fragrances, the industry group Research Institute for Fragrance Materials reviews chemicals and maintains a research database. While there’s certainly a possible conflict of interest there as an industry-tied group, RIFM has an independent review panel of experts. Elsewhere, there is the Cosmetic Ingredient Review, which examines non-fragrance chemicals and provides a public database of scientific research.

So, things aren’t so scary as the film might have us believe.

Other parts of the film are questionable. The film shows the story of a high-school boy who is allergic to Axe body spray. It’s unclear which chemical is causing the allergy—but not made clear in the film is that Unilever, the owner of Axe, is working with the family. (That fact was admitted by Whelan in a post-film discussion.)

Another section of the film praises Proposition 65, a California toxics “right to know” law passed in 1986. But unmentioned by the film is just how bad this law has turned out. It sounds quite reasonable: People must be told if they’re going to be exposed to a chemical that the state thinks may cause cancer or birth defects. The problem is that everything from parking garages to coffee now has a warning label in California. It’s turned into the law that cried wolf. (And it doesn’t help that the law can be enforced by private attorneys—leading to lawyers and environmental groups sending shakedown letters to small businesses.)

All this being said, Stink! is likely to raise concern among viewers with its claims of a lack of transparency or, in the case of fragrance, secrecy about chemicals. And the film has a point. People, for better or worse, want to know more about products they buy. Companies would be wise to be transparent in the face of consumer scrutiny and queries. And putting aside the safety testing done by the aforementioned industry-linked groups, the FDA could certainly do more to test chemicals in consumer products; pending legislation before Congress would do just that, and it has support from both industry and industry critics.

But transparency also goes so far. If Whelan is advocating it in cosmetics, why not elsewhere? We touch chemicals all the time: Paint on walls, treated fabrics in seats at the movie theater, escalator handrails, etc. Should every room we walk into contain a list of every single chemical we’ll be exposed to? Of course not. A “right to know” has practical limits (see Proposition 65, above).

Generally, the personal touch of the film with Whelan and his two daughters is certainly, well, touching, and it is sure to strike a chord with viewers and help the message stick. Further, the fact that people don’t understand chemicals will no doubt help the film gain PR traction. But it’s that very reality that ought to compel a more balanced look from Whelan. That it doesn’t is disheartening. There’s no point in making a stink if what you’re saying doesn’t pass the smell test.